Your cart is currently empty!

Latest

-

Emergency Preparation in Use: The 1964 Alaska Earthquake

When an earthquake struck Alaska in March 1964, Girl Scouts used skills learned at camp and troop meetings.

-

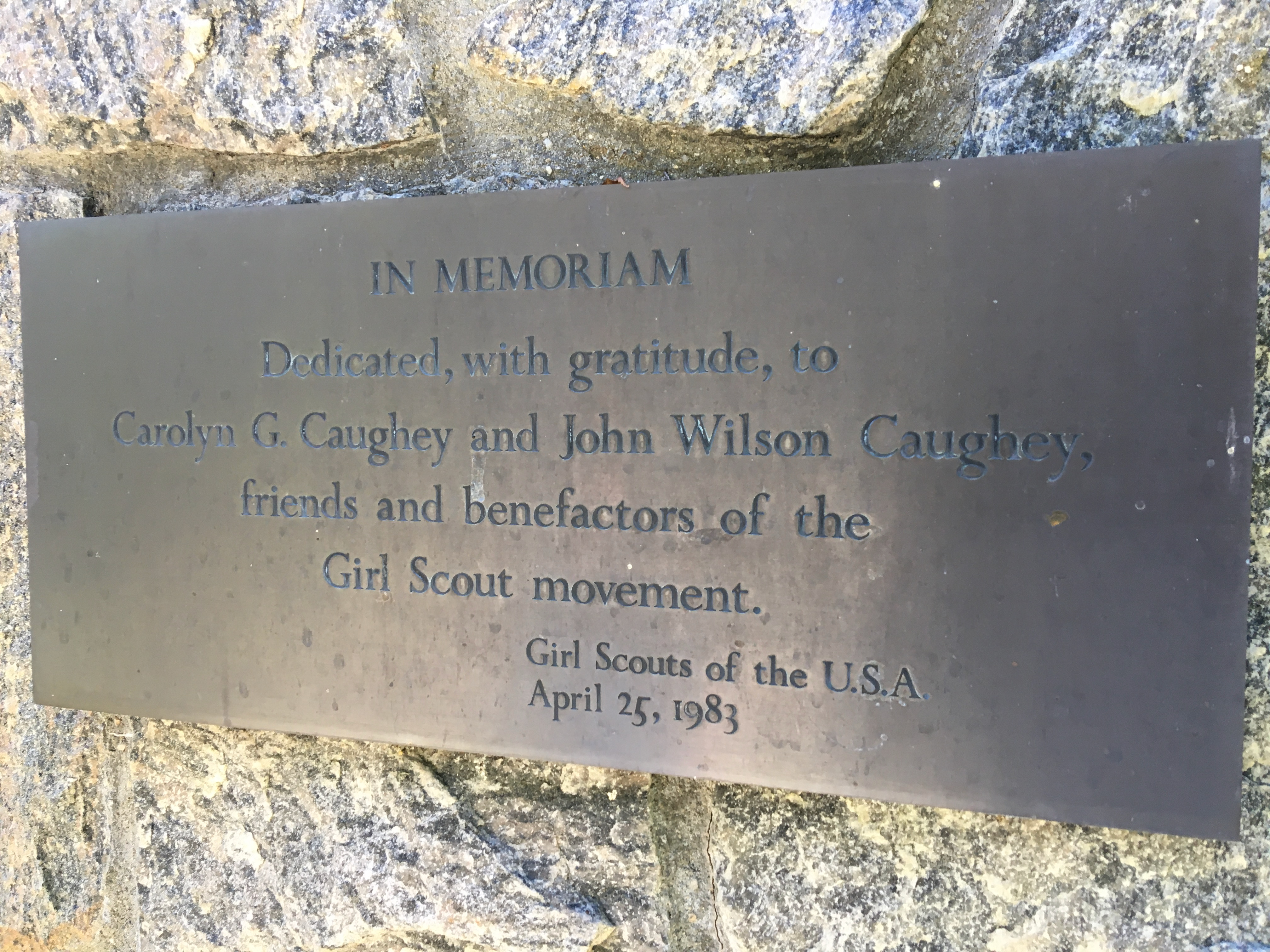

Little House in the Nation’s Capital

The first Girl Scout Little House was dedicated 100 years ago, on March 25, 1924.

VIRTUAL MUSEUMS